Alzheimer's Disease International reports there are 50 million people worldwide living with Alzheimer's Disease (AD), but there remain few approved treatments and no cure. The amount spent to care for patients with AD is over $1 trillion USD, or 1% of global GDP, and experts believe that number will grow to 152 million people by 2050.

Alzheimer's Disease International reports there are 50 million people worldwide living with Alzheimer's Disease (AD), but there remain few approved treatments and no cure. The amount spent to care for patients with AD is over $1 trillion USD, or 1% of global GDP, and experts believe that number will grow to 152 million people by 2050. So where are we in the search for an effective treatment for AD? Can improved preclinical AD models get better candidates into the drug development pipeline?

Current State of AD Drug Development

The report next moves onto diagnosis strategies. Diagnosis includes physical and neurological exams to test reflexes, coordination and memory. Doctors use genetic testing to detect mutations in APOE4, APP, PS-1 and PS-2, and future testing may focus on measuring biomarkers in blood or spinal fluid.

Imaging is becoming more prevalent as a diagnostic tool and recent advances in scanning capability has allowed clinicians to move from well after disease onset to earlier in disease progression and in some cases before disease onset. Early diagnosis can help slow disease onset, yet fewer than 16% of seniors say they receive regular cognitive assessments.

Current AD Therapies

While diagnostics are improving, drug therapies are making slow progress. There is no cure for AD. There are FDA approved drugs that slow advancement of the disease, but do not cure it. The approved drugs can cause severe side effects and are not hugely effective.There are two categories of approved AD drugs: cholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonists.

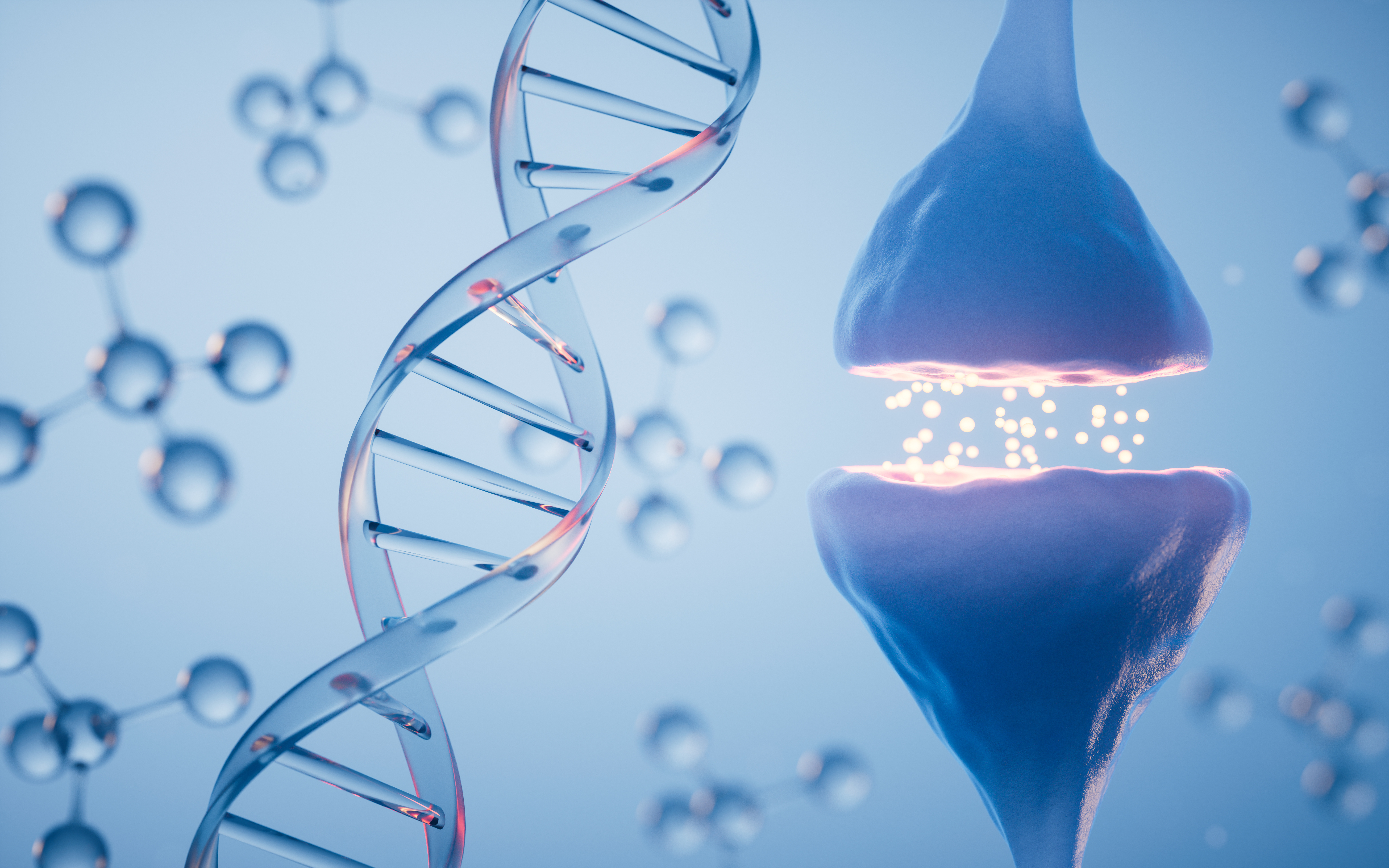

Cholinesterase inhibitors increase the amount of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in the brain. This provides for more neuron to neuron communication. Approved drugs include Eisai's Aricept® (donepezil) and Novartis' Exelon® (rivastigmine tartrate) for all stages of AD. Janssen Pharmaceutical's Razadyne® (galantamine) is approved for mild to moderate AD.

NMDA receptor antagonists alter how neurons communicate. Allergan's Namenda® (memantine) and Namzaric (memantine-donepezil) are both approved for moderate to severe AD. Administration of antidepressant and anti-anxiety medicines can help control behavioral symptoms.

The AD Drug Discovery Pipeline

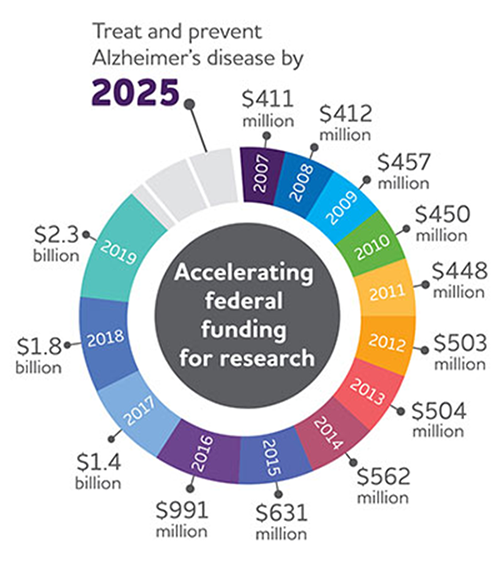

Figure 1: US funding for AD research has continued to grow from just over $400m

USD in 2007 to $2.3b in 2019.

There are over 600 clinical trials in active or development phase and 132 drugs in development. See Figure 2 for a detailed look at where those drugs are being targeted.

The UsAgainstAlzheimer's report The Current State of Alzheimer's Drug Development provides an in-depth analysis of all drugs in clinical development. This is a difficult disease to treat as we do not know the underlying causes of the disease. Most effort has focused on symptoms or pathological outcomes (e.g. Beta amyloid plaques).

AD Animal Models

Figure 2: Biospace. All compounds in AD clinical trials as of February 12,

2019 (the inner ring shows phase 3 agents; the middle ring is comprised

of phase 2 agents; the outer ring presents phase 1 compounds; agents in

green areas are biologics; agents in purple areas are disease; modifying

small molecules; agents in orange areas are symptomatic agents addressing

cognitive enhancement or behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms; the

shape of the icon shows the population of the trial; the icon color shows the

class of target for the agent.). Bolded names represent agents new to that

phase since 2018.

In "The Search for Better Animal Models of Alzheimer's Disease" , the author discusses the benefits and drawbacks of various animal models and notes where animal models used in the study of AD need to go. "While mouse models have provided astounding new insights into disease mechanisms," says Bruce Lamb, a neuroscientist at Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, "they don't reflect the entire biology of the disease." Researchers are now seeking to create AD mouse models that better reflect the more common, sporadic form of Alzheimer's disease, as well as to develop alternative animal models.

In another article, "Preclinical Models of Alzheimer's Disease: Relevance and Translational Validity" the authors note the conceptualization, validation, and interrogation of the current animal models of AD represent key limitations. Rats, wild type and genetically engineered mice, and some non-human primates are the animals typically used to model cognition, dementia and AD. They reference the 180 models from the ALZForum, stating it may be the most models ever generated for a single disease. The authors go on to state that "in reimagining AD based on approaches distinct from the amyloid hypothesis, the key element in their validation is that they can robustly demonstrate the central feature of AD, cognitive failure."

There is an initiative at the National Institute on Aging, called MODEL‐AD, developed in collaboration between Indiana University, the Jackson Laboratory, and Sage Bionetworks, which resulted in the development of the triple transgenic App KO/APOE4/Trem2*R47 mouse model. NIA has funding to generate ten new mouse models per year for the next five years.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)